Our single specialty practice and 172-bed community hospital have been collaborating on performance measures for over three years. Over these years we have monitored several dozen metrics as shown in the Table below. Our Performance Metrics committee including hospital staff, administration and cardiologists meets to formulate, track, and assess metrics on a regular basis.

Table. Examples of Clinical Performance Metrics

General Concepts

Quality of care can be evaluated based upon three different concepts: [1]

1. Structure: characteristics of physicians and hospitals.

2. Process Data: components of the encounter between a health care professional and a patient.

3. Outcome Data: the patient’s subsequent health status.

Our performance metrics were selected based upon mutual consensus for both patient care and hospital process outcomes. There are obviously innumerable clinical metrics that can be selected based upon the hospital and subspecialty. This discussion will focus on the issues can arise during the selection, measuring, and evaluation of these clinical measures.

Choosing Metrics

Many of the metrics we chose were based on cardiac catheterization and electrophysiology laboratories because there were readily available process measures to choose from such as Door-to-Balloon times, case start times, procedural report turnaround times, and pre-procedure antibiotic administration. Care was taken not to lean too heavily on interventionalists or electrophysiologists over the noninvasive cardiologists. Certain clinical measures were not chosen for complicated reasons; for instance, post-procedure lengths of stay were not included in metrics for fear of “quicker-sicker” discharges in an attempt to meet performance goals. Furthermore, we ultimately decided that number of stents used during PCI may not be the most appropriate measure for inclusion in our performance metrics. It must be noted that both post-PCI length of stays and number of stents per procedure are data points included in the American College of Cardiology-National Cardiovascular Data Registry™ (ACC-NCDR).

We relied heavily on the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Core Measures; these are relatively easy metrics to measure and report because they are required by CMS. In addition, our hospital was prepared, and indeed had system personnel in place, to track these Core Measures. A constant issue for discussion in our Metrics Committee was how a particular metric was to be measured. Unless the data element is automatically captured, manual, often laborious and personnel intensive, chart review is undertaken.

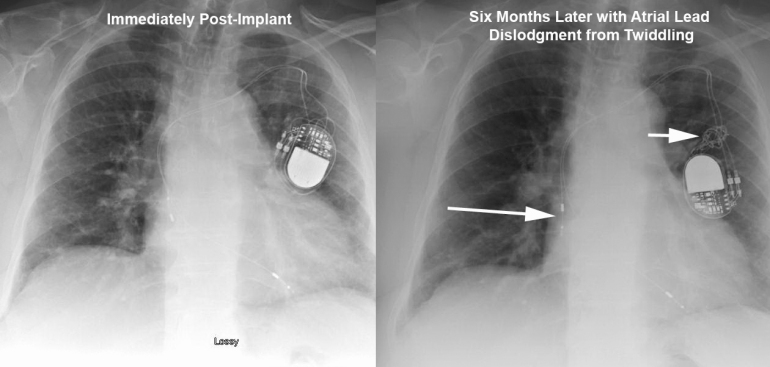

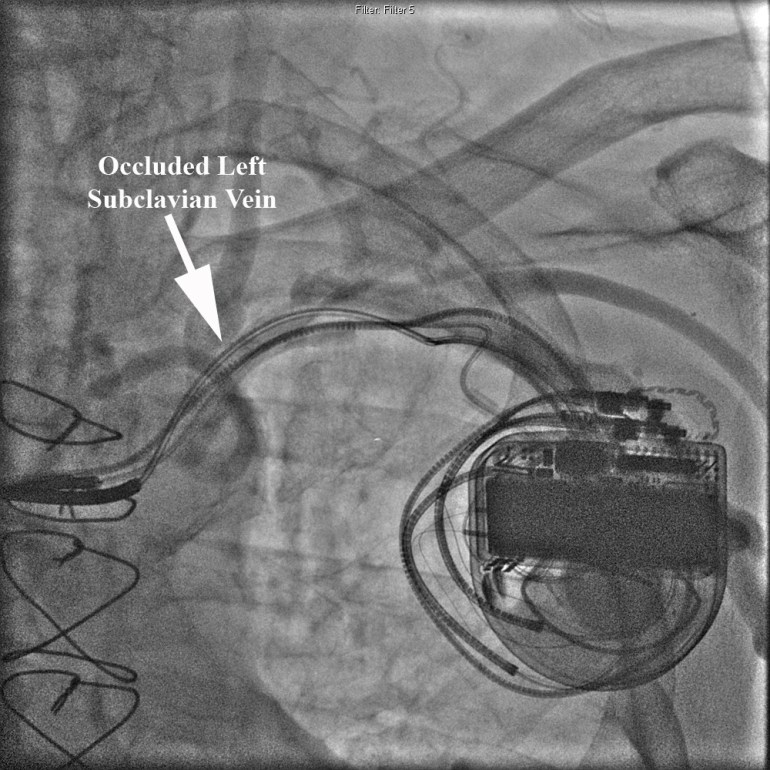

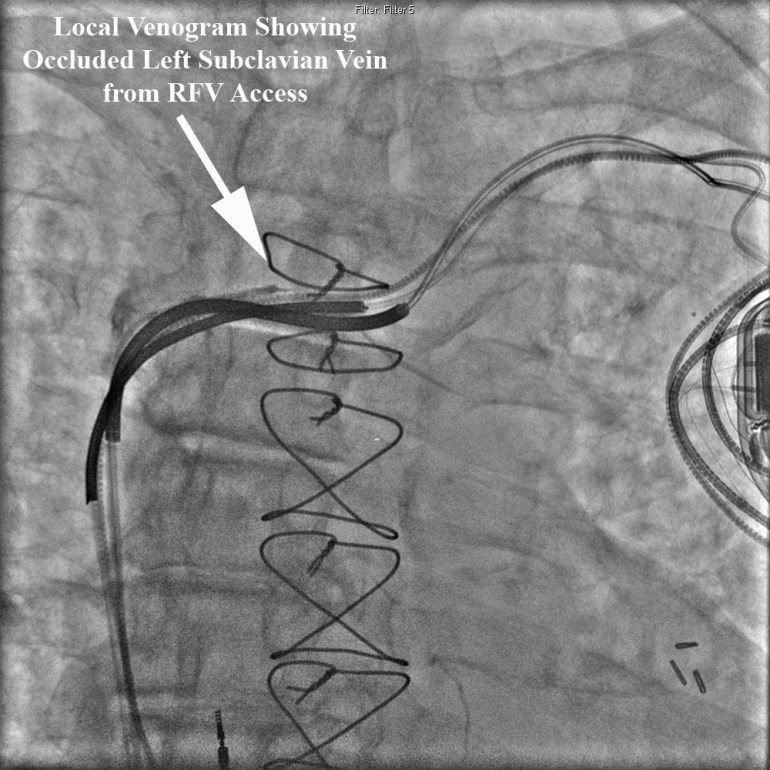

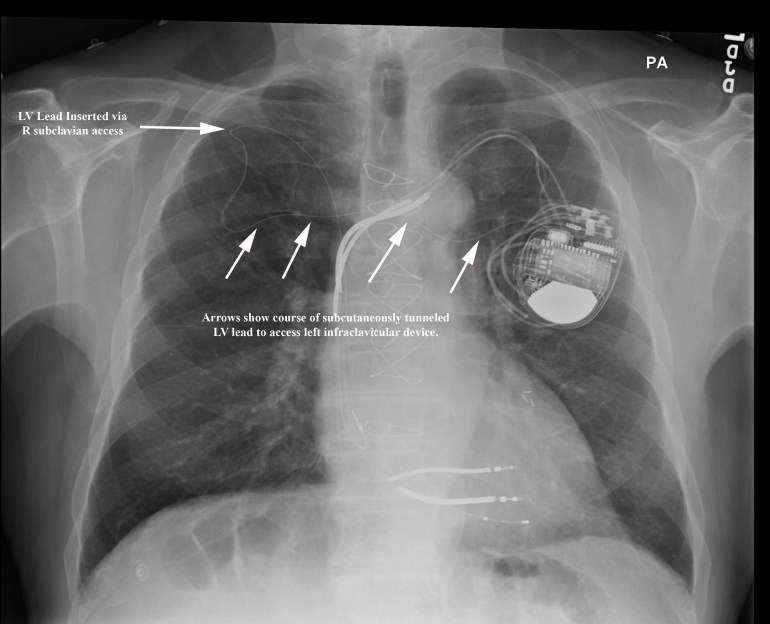

Our community hospital EP program is one of the few programs in the U.S. to publish complication outcomes for pacemaker and defibrillator implantations; with fewer major and minor complications than most published national trials or single academic centers, how should we to choose our goals for complication rates? In reviewing our hospital’s data compared to 50%-ile and 90%-ile centers involved in the ACC NCDR ICD database, it was interesting to see that for Outcome Metric 8 (Incidence of death or any adverse event at implant procedure), Metric 9 (Incidence of Lead Dislodgements All Patients), and Metric 10 (Failure to successfully place LV or coronary sinus lead) the numbers are incredibly low for these 50%-ile and 90%-ile centers (e.g., 0% rate of lead dislodgements?, 1% rate of failure to place LV lead when literature places the average at 8-12%?) and do not reflect complication incidences reported in peer-reviewed literature going back 20 years. These data rely on self-reporting by each center however, economics dictate that only a small minority of sites are audited for data veracity. It becomes difficult for a center to establish a national target for performance (given the current limitation of these national data) rather, local performance must be assessed and risk-stratified; this requires personnel AND advanced statistical methods that may not be readily available for all centers.

Law of Unintended Consequences

It is hard to predict every sequela that may result from a particular clinical metric. An interesting national discussion arose when reviewing Door-to-Balloon Time metrics. [2] The ACC-NCDR database allows centers to exclude patients from Door-to-Balloon Time metrics for reasons such as difficult vascular access or difficulty in crossing culprit lesion. Ellis et al opined that these exclusions were very subjective and could allow centers to “game” the system.

After public reporting of PCI outcomes was instituted, data from the NY PCI registry showed a reduction in mortality from 0.9% in 1997 to 0.58% in 2003. [3,4] Obviously, this may have resulted from improvement in PCI processes however, during that same time period, there was also a 30% decline in patients presenting with cardiogenic shock undergoing PCI. These data may indicate an avoidance of more critically ill patients in an attempt to lower mortality rates.

There are many examples of performance measures that have unintended consequences but vigilant monitoring for unintended consequences should be part of any improvement project. Robust data collection and regular monitoring should help with earlier detection of these unintended consequences.

We Can’t Define Quality but Know It When We See It

I often get calls from family and friends asking about which doctor I would recommend for various types of medical care. We all know the doctors we’d like evaluating our patients (or ourselves) but often this decision is based upon intangible qualities. A recent studied looked at judging surgical skills based upon surgical peer evaluations. [5] Surgeons performing bariatric surgery videotaped themselves performing the surgeries and blinded peers ranked these surgeons on perceived skill. The surgeons with higher ranks in skill experienced fewer perioperative complications. As a practicing clinical electrophysiologist, this type of performance evaluation is appealing because it offers the possibility of scoring performance that may not be accurately reflected by limited outcomes metrics (e.g., ACC NCDR ICD database as described above).

Pay for Maintenance of Quality AND/OR Improvement?

We were at a routine assessment meeting monitoring performance for one of our CV line’s metrics, Door-To-Balloon (DTB) Time; The standard DTB comprises the time it takes to recognize and treat and ST elevation MI with percutaneous coronary intervention. In attempting to tease out our performance (Time Cardiology Notified to STEMI reperfusion) versus the performance of the ER in obtaining and interpreting the electrocardiogram, I performed a quick and dirty power analysis (www.stat.ubc.ca/~rollin/stats/ssize/n1.html) to determine how many patients were required to find a statistically significant difference over a period of a month when our performance improved/deteriorated 5 min (e.g., from 70 to 65minutes Time Cardiology notified to STEMI reperfusion). This power analysis revealed that we would need to include 283 patients to obtain a statistically significant change of 5minutes in this metric. In the prior 11months, our center had 55 included STEMI’s in the metric. It is clear from these data that, although it is nice to see a decrease in 5minutes for this metric, one cannot clearly state this change is due to anything more than chance. Obviously, larger changes (such as changes of 15min or more) do not require as large a sample size, smaller changes seen after a clinical metric has “matured” may not reach statistical significance though one could argue still remain important (at least to our patients!).

We spend much time discussing what to do with metrics that we have improved. For instance, once we reach 100% of patients for a CHF Core Metric such as evidence-based beta blockade, should we then no longer use this metric? For me, it seems ludicrous to abandon a metric because you’ve improved to 100% adherence. Sometimes it seems as if metric achievement is looked at in a vacuum; the goal of performance metric evaluation is to improve patient care. There is precedent that pay for performance models can incorporate both performance improvement AND achievement. [6]

Can Performance-Based Reimbursement “Rescue” Community Hospitals?

Beyond simply improving patient care and healthcare delivery processes, performance metrics may offer respite to the financial concerns of community hospitals that are currently finding it difficult to stay independent. Community hospitals represent more than 85% of all US registered hospitals and are responsible for more than 95% of total hospital admissions. [7] The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission believes that Medicare’s payments should “recognize the value of enhanced patient care provided in teaching hospitals and other settings where residents and other health professionals train when the added value of patient care justifies its higher costs.” [8] Current reimbursement schemes favor academic over community centers without regard to outcomes; nationally recognized academic center in Pennsylvania receives ~39% higher (p=0.019) Medicare reimbursement for an acute myocardial infarction despite 95% of our patients receiving percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) within 90 minutes of arrival (compared with the academic center’s rate of 81%), with no difference in 30-day mortality. [9] There is evidence that community hospitals may 1) have lower care delivery costs, 2) see a more elderly, ill population, and 3) may have fewer complications. [9,10,11,12,13,14] In an era of increasing cost containment and ‘pay-for-performance,’ center-dependent outcomes rather than generalization based on historical assumptions may allow community hospitals to “catch-up” to larger centers in terms of health care reimbursement dollars.

Lessons Learned

1. Only assess metrics that we can directly control and on our patients (though including consults becoming more necessary to get a good denominator of patients).

2. It is necessary to encourage additional resources (money and personnel) to track metrics.

3. Verify data! When we found that 0% of EP dictations were completed on time, we discovered a glitch in our EMR where the time stamps were incorrect.

4. There are two important caveats to remember when measuring quality of care: [1]

a. It is not possible to produce an error free measure of quality of care.

b. Poor measures of quality can unfairly harm institutions and physicians thus efforts should be made to use state-of-the-art measures, even if their use requires additional expenditures.

References

1 Brooks RH, McGlynn EA, Cleary PD, “Quality of Health Care. Part 2: Measuring Quality of Care,” NEJM, V. 335, No. 13 (September 26, 1996), pp. 966-970.

2 Ellis SG, Kapadia S, Heupler F, “The Weasel Clause: Excluding Patients From Door-to-Balloon Analyses,” JACC, V. 56, No. 21 (2010), p. 1763.

3 Khot UN, “Exploring the Risk of Unintended Consequences of Quality Improvement Efforts,” JACC, Vol. 60, No. 9 (2012), pp. 812-813.

4 Resnic FS, Welt FG, “The public health hazards of risk avoidance associated with public reporting of risk-adjusted outcomes in coronary intervention,” JACC, V. 53, No. (2009), pp. 825–30.

5 Birkmeyer JD, Finks JF, O’Reilly A, Oerline M, Carlin AM, Nunn AR, Dimick Janerjee M, and Birkmeyer NJO for the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative, “Surgical Skill and Complication Rates after Bariatric Surgery,” NEJM, V. 369 (October 10, 2013), pp. 1434-1442.

6 Casalino LP, Elster A, Eisenberg A, Lewis E, Montgomery J, Ramos D, “Will pay-for-performance and quality reporting affect health care disparities?” Health Aff, V. 2007, No. 26, w405-w414.

7 Fast Facts on US Hospitals, American Hospital Association website. Available at: http://www.aha.org/aha/resource-center/Statistics-and-Studies/fast-facts.html (accessed July 15, 2008).

8 Wilensky GR, Report to the Congress: Rethinking Medicare’s Payment Policies for Graduate Medical Education and Teaching Hospitals, Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, 1999.

9 US Department of Health & Human Services and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services CMS), Hospital Compare. Available at: http://www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov (accessed February 8, 2010).

10 Newhouse JP. Accounting For Teaching Hospitals’ Higher Costs And What To Do About Them: There might now be more capacity in teaching hospitals than the market is willing to pay for. Health Affairs. 2003; 22(6):126-129.

11 Mechanic R, Coleman K, Dobson A, “Teaching hospital costs: implications for academic missions in a competitive market,” JAMA, V. 280, No. 11 (September 1998), pp. 1015-1019.

12 Zoorob R, Malpani V, Malpani S, “Adult inpatient training for a family practice residency: a university- versus community-based setting,” Fam Med, V. 34, No. 7 (Jul-Aug 2002), pp. 518-521.

13 Lawler FH, Horner RD, Hainer BL, “Process and outcome of critical care provided by community and academic primary care physicians,” Fam Med, V. 21, No. 4 (Jul-Aug 1989), pp. 268-272.

14 Williams JL, Lugg D, Gray R, Hollis D, Stoner M, Stevenson R, “Patient Demographics, Complications, and Hospital Utilization in 250 Consecutive Device Implants of a New Community Hospital Electrophysiology Program,” American Heart Hospital Journal, V. 8, No. 1 (Summer, 2010), pp. 33-39.