Pharmaco-Kinesis Corporation has developed an implantable pump for localized cancer-fighting drug delivery. This first-generation Nano-Impedance Biosensor (NIB) detects vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF-165) which is a biomarker correlating to the presence of a cancerous tumor in the body. The NIB is about the size of an aspirin and can detect VEGF at levels as low as 1 to 10 protein molecules in the billions of molecules present in 1 mL of body fluid. Products using NIB technology could ultimately become available over-the-counter to enable patients to measure biomarkers for cancer and other chronic illnesses. One can envision implantable sensors to track brain natriuretic peptide or troponin to enable instant therapy delivery for cardiovascular patients.

Author: Heart Rhythm Center

Intracardiac Echocardiography May Improve Detection of Implantable Device-Related Endocarditis

A recent article in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology examined the use of intracardiac echocardiography (ICE) to detect cardiovascular implantable electronic device-related endocarditis. The goal of this study from Narducci et al was to compare transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) and intracardiac echocardiography (ICE) for the diagnosis of cardiac device–related endocarditis (CDI). The diagnosis of infective endocarditis (IE) was established by using the modified Duke criteria based mainly on echocardiography and blood culture results.

The group prospectively enrolled 162 patients (age 72 ± 11 years; 125 male) who underwent transvenous lead extraction: 152 with CDI and 10 with lead malfunction (control group). They divided the patients with infection into 3 groups: 44 with a “definite” diagnosis of IE (group 1), 52 with a “possible” diagnosis of IE (group 2), and 56 with a “rejected” diagnosis of IE (group 3). TEE and ICE were performed before the procedure. In group 1, ICE identified intracardiac masses (ICM) in all 44 patients; TEE identified ICM in 32 patients (73%). In group 2, 6 patients (11%) had ICE and TEE both positive for ICM, 8 patients (15%) had a negative TEE but a positive ICE, and 38 patients (73%) had ICE and TEE both negative. In group 3, 2 patients (3%) had ICM both at ICE and TEE, 1 patient (2%) had an ICM at ICE and a negative TEE, and 53 patients (95%) had no ICM at ICE and TEE. ICE and TEE were both negative in the control group.

They found that ICE represents a useful technique for the diagnosis of ICM by providing improved imaging of right-sided leads and increasing the diagnostic yield compared with TEE.

Related articles

- Infective Endocarditis in the U.S., 1998 – 2009: A Nationwide Study (plosone.org)

- Bacterial Endocarditis (insidesurgery.com)

- Steady Rise in Heart Valve Infections Noted in U.S. (news.health.com)

Implantable Blood Test Chip Could Monitor Five Disease States

Image taken from http://www.wired.co.uk/news/archive/2013-03/20/implantable-chip-doctor.

A multidisciplinary Swiss team has developed a tiny implantable chip that can test blood and wirelessly transmit the information to doctors.

Giovanni de Micheli and Sandro Carrara of École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) invented the 14mm-long device. The device is a chip fitted with five sensors and a radio transmitter and is powered via inductive coupling with a battery patch worn outside the body delivering a tenth of a watt in energy. The chip is Bluetooth-equipped to transfer the data picked up by the chip’s radio signals.

The researchers’ goals are to use the chip to monitor five different molecules which may represent five different disease states. This proof-of-concept device has exciting implications for the field of personalized medicine; each person’s biological signals can be recorded and therapy tailored for each individual.

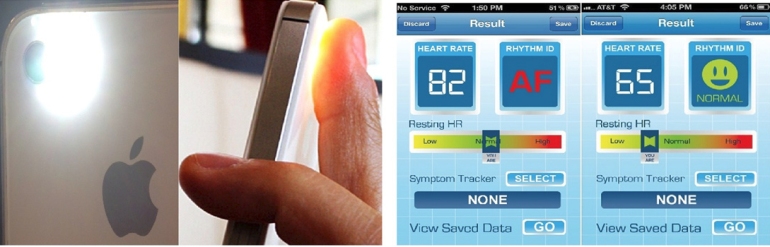

Detection of Atrial Fibrillation using iPhone 4S

Image taken from Heart Rhythm 2013;10:315-319.

Image taken from Heart Rhythm 2013;10:315-319.

A recent article in the Heart Rhythm Journal examines the performance of a smart-phone based application to detect atrial fibrillation. McManus et al conducted real-time analyses using two different statistical methods: root mean square of successive RR differences and Shannon entropy. They found that an algorithm combining both methods demonstrated excellent sensitivity (0.962), specificity (0.975), and accuracy (0.968) for beat-to-beat discrimination of an irregular pulse during afib from sinus rhythm. In an editorial, Dr. Dave Callans (from the University of Pennsylvania) congratulated the authors for this promising new strategy but raised questions on the clinical utility of this application in the absence of better strategies to manage and interpret this new data.

Nanotechnology and Implantable Biosensors

Advances in modern medicine are increasingly relying on electronic devices implanted inside the patient’s body. Nanotechnology allows us to create materials and coatings to construct these devices that are fully biocompatible.

Dissolvable Silk-Silicon Implantable Electronic Devices

Researchers from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign recently developed silk-silicon implantable microcircuits that begin to dissolve two weeks after implantation. These particular implantable devices were designed to produce heat to fight infection after surgery. When the device were implanted in mice, they found that infection was reduced and only faint traces of the device remained after three weeks. These transient implantable devices may have far-ranging applications not only in medicine but in reducing electronic waste.

Ventricular Fibrillation after Elective Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

Case Description:

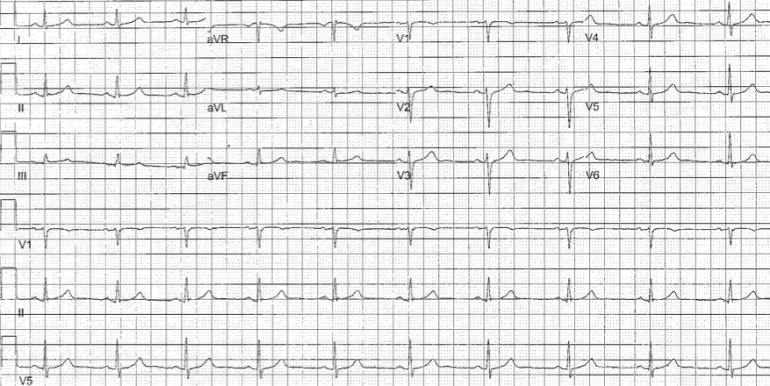

A 60 year old with past medical history of tobacco abuse was admitted for evaluation of chest pain without significant electrocardiogram (ECG) changes, electrolyte abnormalities or troponin elevation. Stress test revealed fixed inferolateral defects with EF44% and associated hypokinesis. Interestingly, an echocardiogram revealed an EF 55-60% with no regional wall motion abnormalities. Catheterization revealed an obstructive lesion in the PDA that had drug eluting stent successfully placed. Approximately one hour after stent placement routine ECG did not reveal any significant acute changes and patient was asymptomatic (see Figure 1). Approximately 150min after stent placement, the patient had an episode of ventricular fibrillation (VF) that required an external DC cardioversion (see Figure 2). Repeat cardiac catheterization did not reveal stent thrombosis or spasm. The patient underwent an uncomplicated single chamber defibrillator placement the following day.

Figure 1. EKG Prior to VF Arrest

Figure 2. Telemetry Strip Showing the VF Arrest

Discussion:

VF arrest during PCI has been reported to have an incidence of 2.1% with higher incidence of VF during right coronary artery PCI. (HUA02) VF arrest during PCI is most commonly precipitated by contrast, ischemia from coronary dissection, embolism, spasm, or catheter manipulation and occurs during the cardiac catheterization. (NIS84) VF arrest after elective percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is uncommon. Indeed, an examination of 19,497 patients undergoing PCI revealed a 0.84% incidence of VF and no episodes of VF arrest temporally unrelated to vessel injection were reported. (ADD05) Survivors of VF arrest in the setting of myocardial infarction (MI) have similar mortality to those not experiencing VF arrest during acute MI. (DEJ09) In contrast, mortality in survivors of in-hospital cardiac arrest has been reported as high as 47% during a median followup of 1.3 years. (HEL11) It is unclear if the mechanism of VF arrest in our patient is secondary to PCI or rather a primary VF arrest. There is a prior report of delayed three vessel coronary spasm in a patient receiving paclitaxel drug-eluting stents however, coronary spasm was demonstrated on repeat catheterization in that report. (KIM05) Our patient did not report any ischemic symptoms preceding his VF arrest (though his EKG had subtle ST changes suggesting possible ischemia) nor did his repeat catheterization reveal vessel thrombosis, spasm, or dissection. Additionally, peri- and post-procedural myocardial injury from slow coronary flow, microvascular embolization, and elevated levels of troponin causing reperfusion tissue damage and cardiac dysfunction leads to worse long-term prognosis than those without myocardial injury (ISH08); our patient did not have significantly elevated pre- or post-procedure troponin levels. The time course of ischemia-induced reperfusion changes is likely less than 30minutes based upon prior experimental models of ischemia. (WIL08) Five minutes of coronary artery occlusion avoids increased risk of ventricular arrhythmias in animals and 30 minutes is appropriate for adequate reperfusion. (DAV81,DAV82,RUF79,WIL08) When the left anterior descending artery is transiently occluded in dogs, there is an initial (t=0-2minutes) small decrease in peak R wave amplitude and conduction velocity followed by a large increase in these indices over the ensuing 1-2minutes. (HOL76) There is a rapid return to baseline when occlusion is released and reperfusion occurs. This biphasic response has also been documented in dogs undergoing circumflex artery occlusions lasting 5minutes. (DAV81,DAV82) However, Ruffy et al (RUF79) found that LAD occlusions for 5 minutes in the dog resulted in a decrease in electrogram R wave amplitudes with no biphasic response. The progressive decrease in R wave amplitude (with the subsequent increase in amplitude) has been demonstrated in isolated rabbits hearts during global ischemia over 10 minutes (KAB89), isolated pig hearts during LAD occlusions for 5 minutesJAN86, and humans subject to 60minutes of unresolved ischemia. (VAI94) Of note, these electrical alterations were rapidly reversible upon reperfusion. (HOL76,RUF79,KAB89,JAN86) In summary then, our patient experienced a VF arrest 150min after elective PCI without conclusive evidence of procedural-related ischemia and well outside the conventional 30min window of reperfusion electrical alterations seen in experimental models. The role of defibrillator implantation as secondary prevention in patients like this is unclear.

References:

HUA02 Huang JL, Ting C-T, Chen Y-T, Chen S-A, “Mechanisms of ventricular fibrillation during coronary angioplasty: increased incidence for the small orifice caliber of the right coronary artery,” International Journal of Cardiology, Volume 82, Issue 3 (March 2002), pp. 221-228.

NIS84 Nishimura RA, Holmes DR Jr, McFarland TM, Smith HC, Bove AA, “Ventricular arrhythmias during coronary angiography in patients with angina pectoris or chest pain syndromes,” Am J Cardiol. V. 53, No. 11 (June 1984), pp. 1496-9.

ADD05 Addala S. Kahn JK, Moccia TF, Harjai K, Pellizon G, Ochoa A, O’Neill WW, “Outcome of Ventricular Fibrillation Developing During Percutaneous Coronary Interventions in 19,497 Patients Without Cardiogenic Shock,” Am J Card, V. 96 (2005), pp. 764-765.

HEL11 Helton TJ, Nadig V, Subramanya SD, Menon V, Ellis SG, Shishehbor MH, “Outcomes of cardiac catheterization and percutaneous coronary intervention for in-hospital VT/VF cardiac arrest, Catheter Cardiovasc Interv, [Epub ahead of print], (July 6, 2011).

DEJ09 DeJong JSSG, Marsman RFHenriques JPS, Koch KT, de Winter RJ, Tanck MWT, Wilde AAM, Dekker LRC, “Prognosis among survivors of primary ventricular fibrillation in the percutaneous coronary intervention era,” Am Heart J, V. 158, No. 3 (September 2009), pp. 467-472.

KIM05 Kim JW, Park CG, Seo HS, Oh DJ, “Delayed severe multivessel spasm and aborted sudden death after Taxus stent implantation,” Heart, V. 91, No. 2 (Feb 2005 Feb), e15.

ISH08 Ishiia H, Amanoa T, Matsubarabv T, Murohara T, “Pharmacological Prevention of Peri-, and Post-Procedural Myocardial Injury in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention,” Current Cardiology Reviews, V. 4. No. 3 (August 2008), pp. 223-230.

WIL08 Williams JL, Mendenhall GS, Saba S, “Effect of Ischemia on Implantable Defibrillator Intracardiac Shock Electrograms,” J Cardiovasc Electrophysiology, Vol. 19, No. 3 (March 2008), pp. 275-281.

DAV81 David D, Naito M, Chen CC, Michelson EL, Morganroth J, Schaffenburg M, “R-wave Amplitude Variations During Acute Experimental Myocardial Ischemia: An Inadequate Index for Changes in Intracardiac Volume,” Circulation, V. 63, No. 6 (June 1981), pp. 1364-1370.

DAV82 David D, Naito M, Michelson EL, Watanabe Y, Chen CC, Morganroth J, Schaffenburg M, Blenko T, “Intramyocardial Conduction: A Major Determinant of R-wave Amplitude During Acute Myocardial Ischemia,” Circulation, V. 65, No. 1 (January 1982), pp. 161-167.

RUF79 Ruffy R, Lovelace DE, Mueller TM, Knoebel SB, Zipes DP, “Relationship between Changes in Left Ventricular Bipolar Electrograms and Regional Myocardial Blood Flow during Acute Coronary Artery Occlusion in the Dog,” Circulation Research, V. 45, No. 6 (December 1979), pp. 764-770.

HOL76 Holland RP, Brooks H, “The QRS Complex during Myocardial Ischemia,” Journal Clinical Investigation, V. 57 (March 1976), pp. 541-550.

KAB89 Kabell G, “Ischemia-Induced Conduction Delay and Ventricular Arrhythmias: Comparative Electropharmacology of Bethanidine Sulfate and Bretylium Tosylate,” Journal Cardiovascular Pharmacology, V. 13, No. 3 (1989), pp. 471-482.

VAI94 Vaitkus PT, Miller JM, Buxton AE, Josephson ME, Laskey WK, “Ischemia-induced changes in human endocardial electrograms during percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty,” American Heart Journal, V. 127, No. 6 (June 1994), pp. 1481-1490.

JAN86 Janse MJ, “Electrophysiology and electrocardiology of acute myocardial ischemia,” Can J Cardiology, Supp. A (July 1986), pp. 46A-52A.

The Possibility of Biological Pacemakers: Can We Eliminate Electronic Pacemakers?

Current pacemaker therapy requires the use of an electronic pacemaker and implantable leads (What is a Pacemaker? ). There have been reports of leadless pacemakers that use an implantable yet leadless means to pace the heart (Nanostim Leadless Pacemaker). A group has recently reported results of their study examining the implantation of pacemaker-related genes. (Biological Pacemaker using Genes) A biological pacemaker has the advantages of no indwelling hardware and may eliminate risk of infection from traditional pacemakers.

Cingolani et al utilized a right femoral vein transvenous approach to deliver pacemaker-related genes to the atrioventricular (AV) junction. Genes expressing dominant-negative inward rectifier potassium channel (Kir2.1AAA) and hyperpolarization-activated cation channel (HCN2) genes were used; these are responsible for the pacemaker current (If, HCN2) and suppression of the inward rectifier current (Kir2.1). This overexpression results in junctional pacemaker activity for up to 2weeks. They found a septal activation pattern similar to those seen during sinus rhythm; thus, this biological pacemaker may not cause dyssynchrony seen in right ventricular (RV) apical pacing.

Aside from gene overexpression, pluripotent stem cells and specific factors (T box transcription factors) may offer biological pacemaker activity as well. Obviously, these are all preclinical techniques that may offer an exciting alternative to current electronic, implantable pacemakers.

Can Wireless Charging be a Disruptive Force in the Medical Device Industry?

Nokia has introduced a smart phone that can charge itself wirelessly. (http://www.nokia.com/global/products/lumia/) It is safe to assume that Nokia uses induction based technology to charge the phone. The phone (equipped with a special receiver) is placed on a mat that generates an electromagnetic field. The phone’s special receiver uses this electromagnetic field to charge the phone’s battery. This technology can only power one device at a time and may generate heat during the charging process.

Recently, IDT and Intel partnered to announce the development of an integrated transmitter and receiver chipset for Intel’s wireless charging technology based on resonance technology. (IDT and Intel Partnership) Magnetic resonance uses electrical components (a coil and a capacitor) to create magnetic resonance. This resonance can then transmit electricity to the receiver (device to be charged) from the transmitter (charging base). Magnetic resonance can power multiple devices at a time and may not generate excessive heat. A nice summary of this technology is available at Fujitsu Summary of Wireless Charging.

These technologies can be disruptive forces in the medical device industry that rely on battery depletion and replacement for subsequent sales (e.g., pacemakers, defibrillator, and noncardiac pulse generators). The device company that incorporates wireless charging into their devices may minimize replacement procedures for patients (and limiting procedural risk) while at the same time stabilizing their market position. Future device upgrades may be software upgrades and licensing that can be performed wirelessly without need for invasive procedure.

Implantable Biosensor Can Measure Glucose in Sweat and Tears

Researchers at the Fraunhofer Institute for Microelectronic Circuits and Systems IMS in Duisburg have developed an implantable biosensor that can measure glucose in sweat or tears obviating the need for needlesticks. An electrochemical reaction using glucose oxidase that converts glucose into hydrogen peroxide; this concentration can be measured with a potentiostat and these measurements are used to calculate the glucose level. This biosensor has incorporated the entire diagnostic circuit into a fully implantable tiny sensor. The biosensor can transmit the data via a wireless interface to a mobile receiver or even smart phone.