Both non-irrigated and irrigated tip catheters for radiofrequency ablation (RFA) can cause steam pops with abrupt impedance rises probably owing to release of steam from excessive heating below the surface. [1] Saline irrigation maintains a low electrode-endocardial interface temperature during RFA at higher powers, which prevents an impedance rise and produces deeper and larger lesions. But you can see higher temperatures deeper in the cardiac wall (~3.5mm) than at the electrode-endocardial interface. This is thought to be due to direct resistive heating rather than by conduction of heat from the surface. [1] This excessive heating may cause water in the endocardium to vaporize into a gas bubble. Continued ablation (and hence heat formation) can cause this bubble to expand with increased pressure. If this gas bubble suddenly bursts inward toward the endocardium or outward to the epicardium, it can cause an audible “pop.”

The following video (courtesy of Dr. Dave Schwartzman, UPMC, Pittsburgh, PA) shows an ex vivo tissue preparation and formation of a steam pop during application of RFA. A significant concern of steam pops is the risk of cardiac perforation. Perforation with tamponade was seen in 1 of 62 (2%) VT ablations where a steam pop occurred. [2] The RFA applications with steam pops had a higher maximum power but did not differ in maximum catheter tip temperature. It reasons that steam pops in the pulmonary veins or atria may pose higher risk of perforation.

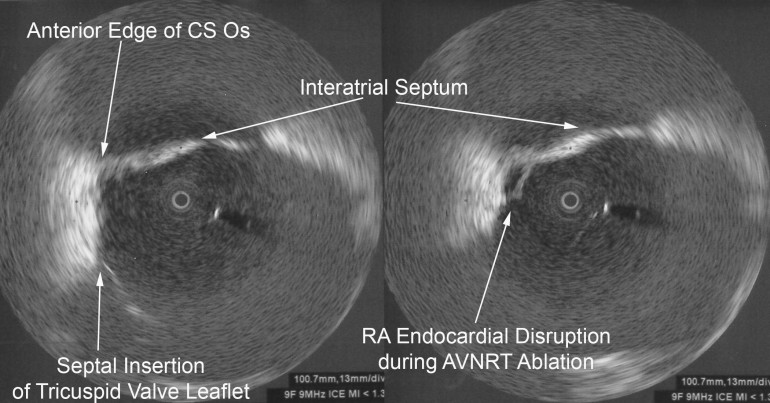

A middle-aged male with no significant medical history underwent an EP study and ablation for typical atrioventricular node reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT). The AVNRT ablation was being guided by radial intracardiac echocardiography. RFA (using power-control setting) is attempted at the anatomic location of the slow AVN pathway region at the anterior edge of the CS os near the septal insertion of the tricuspid valve leaflet (see Figure). Power was titrated from 5W to 30W but required 40W to demonstrate an accelerated junctional rhythm associated with ablation success. A steam pop was felt and evidence of a small defect in the endocardium in the region was noted on radial ICE as shown in Figure. There was no obvious microbubble formation evident on radial ICE prior to the steam pop. Subsequent echocardiograms demonstrated no evidence of perforation or tamponade and patient was asymptomatic at follow-up several weeks later.

References:

1 Nakagawa H et al, “Comparison of In Vivo Tissue Temperature Profile and Lesion Geometry for Radiofrequency Ablation With a Saline-Irrigated Electrode Versus Temperature Control in a Canine Thigh Muscle Preparation,” Circulation (1995), V. 91, pp. 2264-2273.

2 Seiler J et al, “Steam pops during irrigated radiofrequency ablation: feasibility of impedance monitoring for prevention,” Heart Rhythm (Oct 2008), V. 5, No. 10, pp. 1411-1416.